On 13th February 2015 I was diagnosed with Stage 3 colorectal cancer. At the beginning of August this year my treatment was complete. After nearly two years of grappling with a life-threatening illness, whilst at the same time hanging on to the bones of a business that I had set up just eighteen months before diagnosis, it is time to embrace the new normal. This is my story about cancer and entrepreneurshit.

Cancer

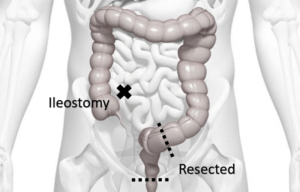

My treatment began quickly after diagnosis. Between March and April 2015 I received 26 daily treatments of radiotherapy with Capecitabine oral chemotherapy. After radiotherapy had finished, the tumour’s response was monitored and observed for three months. It shrank significantly during that period but it needed to be removed. Locally-advanced colorectal cancer necessitates complete removal of the rectum and on 4th August 2015 I underwent a 6 hour operation at Barnett Hospital, during which my surgeon removed (resected) the bowel and reconnected it back together (anostomosis).

The chemotherapy regime that I received was given in an effort to mop up any cancer cells that might have escaped into my system and was scheduled to begin just one month after the operation. But the body doesn’t heal well when it’s being pumped full of cell-killing chemotherapy drugs, so a temporary ileostomy was also created during the operation to protect the internal wound and allow it plenty of time to heal. An ileostomy is a diversion of the small intestine through an opening in the stomach. It stops digestive waste passing through the full length of the intestines. Instead the waste comes out through the diversion in the stomach and is collected in an ostomy bag.

The chemotherapy regime that I received was given in an effort to mop up any cancer cells that might have escaped into my system and was scheduled to begin just one month after the operation. But the body doesn’t heal well when it’s being pumped full of cell-killing chemotherapy drugs, so a temporary ileostomy was also created during the operation to protect the internal wound and allow it plenty of time to heal. An ileostomy is a diversion of the small intestine through an opening in the stomach. It stops digestive waste passing through the full length of the intestines. Instead the waste comes out through the diversion in the stomach and is collected in an ostomy bag.

Chemotherapy began 4th September 2015 and over four and a half months I received 8 rounds of 48 hour FOLFOX infusions. I’ve written before about my journey up until I finished my chemotherapy finished. It was a brutal onslaught. The drugs attack the body’s cells almost indiscriminately. My mind and body were a mess. When chemotherapy finished at the end of December 2015 there was still another operation to come. Six months later and exactly one year to the day after my first surgery, on 4th August 2016 I returned to Barnett Hospital for the follow up operation to reverse my temporary ileostomy.

Life with an ostomy bag is awkward and psychologically weird, especially when combined with everything else that goes on in the mind of a cancer patient. The smile on my face tells the story of a successful operation and a very relieved patient. With no more treatment hanging over me and the dreaded bag gone, I felt like I had got my life back. The challenges of having a large section of the bowel removed became immediately apparent but are a very small price to pay for being alive.

I have felt my body regenerating ever since chemotherapy ended. My chemo-brain has resharpened. My hair has thickened and is weirdly more curly than it was before. The neuropathy in my hands and feet got worse before it improved but feeling has returned to my fingers. I’m still waiting on my toes! My mental well-being feels balanced. The darkest places will never be forgotten but they are at least feel far behind me. A psychologist recently told me that I was suffering from Posttraumatic Growth:

“A positive psychological change experienced as a result of adversity and other challenges in order to rise to a higher level of functioning. These sets of circumstances represent significant challenges to the adaptive resources of the individual, and pose significant challenges to individuals’ way of understanding the world and their place in it. Posttraumatic growth is not about returning to the same life as it was previously experienced before a period of traumatic suffering; but rather it is about undergoing significant ‘life-changing’ psychological shifts in thinking and relating to the world, that contribute to a personal process of change, that is deeply meaningful.”

This is a perfect summary of how I feel. It would be ridiculous to say that I am glad I have had this experience but I don’t regret it either. My brain does function on a different plane. I really do feel like I have a new understanding of the world and my place in it. Life will never be the same again and my thinking on many matters has substantially shifted. It’s not just what happens to us that counts – it’s what we think happens to us.

Entrepreneurshit

The title of this post is a tongue in cheek nod to my life as an entrepreneur whose bowels will never be the same again. The day to day reality can be very unpleasant, but I only have to remind myself that I have survived cancer and that I’m get physically and mentally stronger each day. Fortunately there’s plenty of time to do that when you’re sat on the toilet for the twentieth time in a day.

The title is also a recognition of challenges that entrepreneurs face, inspired by Mark Suster’s post on the theme: Entrepreneurshit – The Blog Post on What It’s Really Like. Mark is a successful British entrepreneur, turned venture capitalist, who now lives in San Francisco. I remember reading his post when I first left the corporate world to set up my own business. It is about what entrepreneurship is really like. I may not be building a Unicorn, but it resonated because I had a strong suspicion I was on course to discover what he said to be true.

I chose entrepreneurship because it represented freedom and creativity. An opportunity to operate outside the constraints of a traditional career, to choose my own direction and set my own rules, control my own destiny and be self-reliant. To create something new. On top of that I could wear my Air Max to work and I wouldn’t have to shave every morning. I could live the life that I wanted to lead.

I quickly learned that the trade off for freedom is significantly increased uncertainty. Entrepreneurial upside brings with it lingering downside. Entrepreneurship is an imprecise pursuit. Hard work does not correlate with success and salary to the extent that it does in other jobs. Money does not appear in your bank account at the end of each month unless you make a concerted effort to put there, which is very hard to do when you still haven’t worked out what your business model is.

What if my idea doesn’t work? What if I run out of money? What will people think of me? What will I think of myself? What does the future hold? Any entrepreneur knows that these are just a few of the questions haunting you on a daily basis, paralysing the creativity you strive for. As my confidence bias wore off, I realised just how anxious and fearful I was. I was everything that Mark described. Suddenly, eighteen months into my entrepreneurial journey, I was also a cancer patient. My sense of uncertainty about the future had just gone off the chart.

The New Normal

A cancer diagnosis serves up one of the most brutal lessons in just how uncertain life it. You are exposed you to your deepest, darkest, most primordial fears. One word rips your world apart and propels you into another, far more desperate one.

I embarked on a voyage of incredible self-discovery and learning. I studied the science behind my illness but also what my brain was doing and why. I now understand just how much humans hate uncertainty. It’s not our fault, evolution has wired us this way. Peter Bevelin explains it best in his brilliant book Seeking Wisdom: From Darwin to Munger:

We don’t like uncertainty or the unknown. We need to categorize, classify, organise and structure the world. Categorising ideas and objects helps us to recognise, differentiate and understand. It simplifies life. To understand and control our environment helps us to deal with the future. We want to know how and why things happen and what is going to happen in the future.

The ancient inner limbic part of our brain is designed to keep us alive by looking for threats and responding to them. Even if we are not sure if something is a threat, our brain often tells us that it is because it’s better to assume so and stay alive than risk it and not get a second chance.

A sense of uncertainty translates into a strong threat or alert response in our limbic system, at the expense of our neo-cortex, the thinking part of our brain. Uncertainty is like a type of pain and therefore something to be avoided. Certainty, on the other hand, feels rewarding so we navigate towards it. In the context of this post, it’s an important reason why the majority of people shun the relative uncertainty of entrepreneurship in favour of perceived corporate certainty. If nothing else, it’s just easier on the brain.

Our brain is wired to perceive before it thinks – to use emotion before reason. As a consequence of our tendency for fear, fast classifications come naturally. Limited time and knowledge in a dangerous and scarce environment made hasty generalisations and stereotyping vital for survival. Waiting and weighing evidence could mean death. Don’t we often draw fast conclusions, act on impulse and use our emotions to form quick impressions and judgements?

My illness has gone a long way to liberate me from uncertainty and my anxious disposition, and understand the significant flaws that can exist in our thinking process particularly when we are in stressful situations. We try to predict and plan the future in order to avoid the pain of uncertainty, but there is nothing like a cancer diagnosis to make you truly appreciate that life is inherently uncertain and that there is very little you can do about it. It follows that if uncertainty diminishes our ability to think clearly, then leaning in and working with it should put us in a position of significant advantage. I don’t fight uncertainty like I used to anymore. Over-riding the brain’s chemistry is not easy but I do what I can to flip it on its head and adopt a thinking style that exploits it.

A cancer diagnosis also leads you to ask a lot of questions. Most frequently I ask myself why did I get away with this when others are not so lucky? Superior medical ability was pivotal to my successful outcome but the role of luck cannot be under-estimated. The cancer journey is a confusing one and it has given me a new perspective on the role of luck in life. When I was first diagnosed, it was impossible not to feel like the unluckiest person in the world. As the journey progressed, and my treatment options and prognosis became clearer, I began to feel like the luckiest person in the world: there was a very good chance that I was going to get away this and walk away almost in one piece. But why me? Feelings of unluckiness turned to luckiness, and then to guilt as I watch other young people lose their struggle with serious illnesses.

I don’t spend much time worrying about the cancer returning; the likelihood is low and thinking probabilistically is another mental skill I am working on. It is the enormity of the whole experience that sometimes overwhelms me. What is the meaning of life, the nature of the human condition, the point of it all? I don’t know the answer to those questions. What I do know is that I am coming out the back of this experience and I am in a very good place. The other month I retraced my cancer journey in one day and documented it in a Tweetstorm, ending the day with a consultation with my medical team and a formal ‘all clear’. Now it’s time to embrace uncertainty, appreciate the role of luck and rebuild my life and business. This is my new normal and I couldn’t be happier.

- My Oncologist Dr. Rob Glynne-Jones & Nurse Specialist Angela Wheeler

- Mom & Dad X

[subscribe_bar]