Successful businesses today must be technology-enabled and able to compete in a global marketplace. Older businesses must adapt or die. Janesville: An American Story by Amy Goldstein explores what happens to businesses that don’t adapt and the impact upon the places and individuals that get left behind. An insightful case study of a medical technology company that is incentivised to move to the town, raises the question of whether or not technology can save the American Dream: “the opportunity for prosperity and success, as well as an upward social mobility for the family and children, achieved through hard work in a society with few barriers” (Wikipedia).

Janesville tells the story of what happens to an industrial town in the American heartland when its main factory shuts down. The account goes a long way to explaining systemic challenges that are leading to social, economic and political upheaval and broader questions around whether or not technology can save the American Dream.

I help executives navigate business and personal growth in a complex world. Sign up to receive my monthly newsletter The Future Of Leadership and follow me on Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.

Janesville: A Short History

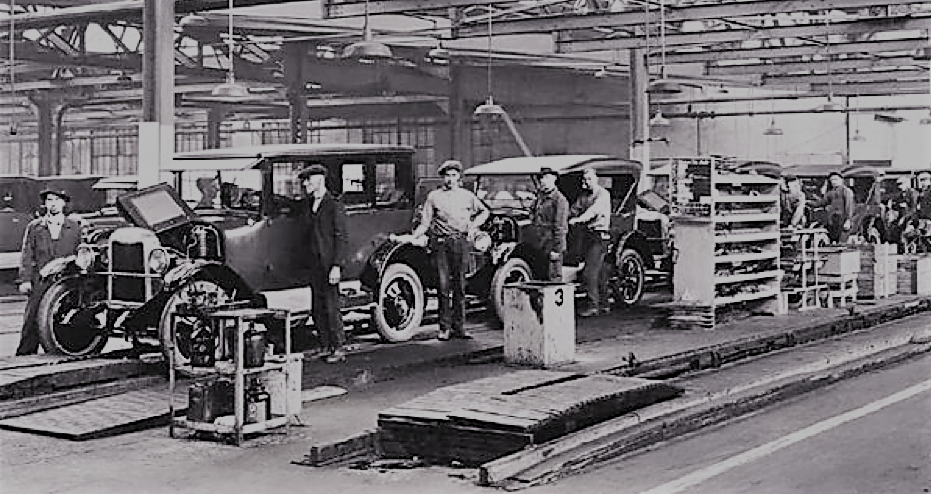

General Motors started churning out Chevrolets in Janesville on Valentine’s Day of 1923. For eight and a half decades, this factory, like a mighty wizard, ordered the city’s rhythms. The radio station synchronized its news broadcasts to the shift change. Grocery prices went up along with GM raises. People timed their trips across town to the daily movement of freight trains hauling in parts and hauling away finished cars, trucks and SUVs. By the time the plant closed [on December 23rd 2008], the United States was in a crushing financial crisis that left a nation strewn with discarded jobs and deteriorated wages.

The work that vanished – as many as nine thousand people lost their jobs in and near this county seat in 2008 and 2009 – was among 8.8 million jobs washed away in the Unites States by what came to be known as the Great Recession. This mighty recession – the worst economic times since the 1930s – stole American jobs, not in a single industry, not in a cluster of ill-fated communities, but up and down the economic ladder, from the East Coast to the West, in places that had never been part of the Rust Belt or any other bad economic belt and had never imagined that they would be so bruised. Places like Janesville.

[The citizens of Janesville] set out to reinvent their town and themselves. Over a few years, it became evident that no one outside – not the Democrats or the Republicans, nor the bureaucrats in Washington, not the fading unions nor the struggling corporations – had the key to create the middle class anew. The deserted assembly plant embodies their dilemma: How do you forge a future – how do you even comprehend that you need to let go of the past – when the carcass of a 4.8 million square foot cathedral of industry still sits in silence on the river’s edge?

Janesville: An opportunity for personal reinvention?

Training people out of unemployment is a big, popular idea. In fact it may be the only economic idea on which Republicans and Democrats agree, anchored, as it is, in the abiding cultural myth, going back to America’s founding, of this as a land that offers its people a chance at personal reinvention. [However] the evidence is thin that job training in the United States is an effective way to lead laid-off workers back into solid employment.

By 2011, three years after the assembly plant and its supplier companies shut down, the impact of a sweeping retraining programme launched in Janesville became evident. It wasn’t looking good.

Counterintuitive as it may seem, the out-of-a-job workers who went to Blackhawk [the local Technical College] are working less than the others. Nearly two thousand laid-off people in and around Janesville have studied at Blackhawk. Only about one in three has a steady job compared with about half the laid-off people who did not go back to school. Besides, the people who went back to Blackhawk are not earning as much money… the people who have found a new job without retraining are being paid, on average, about 8 percent less than they were paid before. But those who went to Blackhawk are being paid, on average, one third less than before.

The retraining gospel that the federal government and the Job Center’s own caseworkers have been spreading is based on a rock-bottom premise that hasn’t turned out to be true – at least, not yet. The premise is that this recession would be like past recessions and that jobs would come back at the pace they have before. It is not happening… the Job Center, with good intentions but wrong expectations, has sent people into a double whammy. They lost their jobs. They went to school to equip themselves with new skills, and they still can’t find jobs.

Janesville: The Domino Effect

In the shadows of town, hundreds of teenagers are becoming victims of a domino effect. These are kids whose parents used to scrape by on jobs at Burger King or Target or the Gas Mart. Now their parents are competing with the unemployed autoworkers who used to look down on these jobs but are grasping at any job they can find. So, as middle-class families have been tumbling downhill, working-class families have been tumbling into poverty. And as this down-into-poverty domino effect happens, some parents are turning to drinking or drugs. Some are leaving their kids behind while they go looking for work out of town. Some are just unable to keep up the rent. So with a parent or on their own, a growing crop of teenagers is surfing the couches at friends’ and relatives’ places – or spending nights in out-of-the-way spots in cars or on the street.

Janesville: Technology will save us

In 2012, SHINE Medical Technologies was a startup company producing a medical isotope from uranium, used for various diagnostic imaging purposes including the detection of heart disease and cancer metastases. Founded and run by Greg Piefer, SHINE had just a dozen employees, insufficient investment capital, a never-before-used isotope-making process and considerable and regulatory obstacles in its way to achieving a federal license. However, Janesville had big hopes for SHINE. It offered the company a $9 million package of support from the city government to incentivise it to locate in Janesville, almost a quarter of it’s $42 million annual budget.

Mary Willmer, co-Chair of Rock County 5.0 (the private sector organisation set up to promote economic development) considered SHINE to be a game-changer.

Ever since the assembly plant closed just over three years ago, she and local economic development officials have been working to court businesses that could lift up and diversify Janesville’s sunken economy. Paul Ryan, too [Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, Ryan is also the Republican Member of Congress for Wisconsin and was born in Janesville]. From Capitol Hill and when he is back home, Paul has been making business recruitment calls anytime that Rock County’s economic development manager has sent him a lead and the name of a CEO to contact. “In this economy? I’m not taking the risk”, is the reply that Paul has heard from CEOs more times than he care to remember.

Willmer’s belief was that Janesville needs to update its identity from an old auto town to a twenty-first century centre of advanced manufacturing.

What a waste that the University of Wisconsin-Madison has a research park, just forty-four miles northwest of Janesville, filled with startups dreaming up entrepreneurial innovations in the life-sciences and other technologies, and none of the manufacturing spun off from these innovative ideas has ever come to Janesville.

Her belief in the game-changing potential of SHINE was undimmed by certain facts.

SHINE would not bring many jobs. Piefer has been saying that he’d need 125 employees – a tiny fraction of the jobs that went away. And the soonest those jobs would arrive is three years from now, and it could be later, unless all goes smoothly with investment capital and federal reviews. And whenever he’s been asked, Piefer has side-stepped the question of how many of those jobs could be filled by people from Janesville, instead of people from elsewhere with greater scientific expertise… Still the salaries Piefer has been talking about – $50,000 to $60,000 a year – have stirred hope across the city, when so many are working for so much less than their wages in the past.

Janesville: American Dream or Nightmare?

Writing in the New Yorker in May 2017, Joshua Rothman provides an update on Janesville’s fate.

Today, there is a new normal in Janesville. Unemployment is low—just four per cent—but the jobs that are available don’t pay well, and the standard of living has declined. Thousands of families have fallen into working poverty. Socially, there is a void where factories and unions once created a sense of common life. “Janesville has been left to rely to a considerable extent on its own resources,” Goldstein concludes. Luckily, “those resources include more generosity and ingenuity—and less bitterness—than in many communities that have been economically injured.”

And what of the fate of SHINE technologies? At the time of the book’s publication in 2017, the startup had:

Passed tough regulatory hurdles and won a construction permit from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. It is behind schedule. Having hoped to start manufacturing in 2015, it is now aiming for late 2019. Yet in a tangible step, SHINE has just moved its corporate headquarters to downtown Janesville, with still more help from the city – another nearly $400,000 in incentives to renovate office space. SHINE expects to employ 150 people.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like:

Interested in the impacts of technology on human being? Read one of the most popular articles on my site What is the impact of technology on babies & young children?

In another post I explore how your smartphone impacts your brain.

I help executives navigate business and personal growth in a complex world. You can follow me on Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram.